It’s gotten quieter around the Belt and Road Initiative, but don’t be fooled. It doesn’t mean there is less ambition to build it out further, certainly not by China. The problem with the mega project still is that it has remained an enigma to many. What is it meant to be? What is it meant to achieve? How is it being financed? Is it even possible to pull it off? And most importantly, will China’s lobby be enough to rally all existing and prospective stakeholders to lend the necessary support?

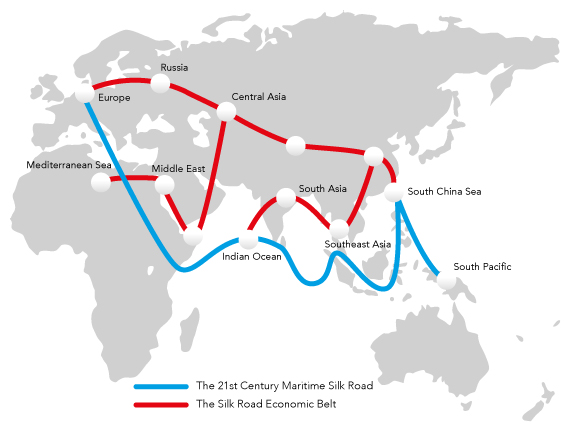

Well, we don’t yet know the answers to all those questions, but whatever it will be eventually, it is certainly one of the most visionary projects, if not the most visionary project, of our time. In a nutshell, it is laid out as connecting and bringing together the entire Eurasian plate, the Middle East, and Africa. Beijing is clearly in the driver’s seat and very systematic in building its structure around land and maritime trade routes, as well as the AIIB as the centre-piece of a development institution to back it up financially.

But what drives China doing all this? It is obvious from the country’s millennial history that it is unlikely to be for imperial reasons. So, what is it then? Let’s take a stab at it: One, there is the old ballade of China wanting to trade with the world, and countries willing to trade with each other are less likely to go to war… there sure is something to it, and its validity will be predominant in the case of China’s relationship with South-East Asia.

But two, and more importantly, it is an existential project for China. The country’s population may not grow any longer and be surpassed by India’s in due course, but China needs space to develop and modernise. To be contained by all these strange strategies instigated by Washington in an alliance with Japan, Australia, and others is not conducive to what China wants to do with its country and society.

Three, China is keen on expanding its ecosystem. Due to its own emerging process, it has a deep understanding of how economic development in South-East Asia, Central Asia, and Africa works. It also has this massive excess capacity with regard to infrastructure and housing construction, the capacity that will only grow as China steps up the modernisation ladder. It will increasingly be idle and in need to be employed, and nowhere better is this done than on the Eurasian plate and in Africa.

And we are seeing initial steps. Think of the Eastern Economic Corridor that runs from China through Pakistan to the Indian Ocean. Think of the new high-speed train line cutting through Laos into Thailand. Think of the port constructions in Sri Lanka and the Philippines. Or as one example further away, think of Ethiopia, one of the 5 African countries China is investing heavily in, ranging from business parks around Addis Abeba to the brand-new train line connecting the capital with Djibouti.

No wonder, and much to the dismay of the rest of the world, that China has also been building out its naval and military presence to protect its investments and trade routes. Djibouti is China’s first international base. Gwadar in Pakistan, a deep-water port where that Eastern Economic Corridor culminates into, will not just serve commercial purposes. Think also of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port leased by the Chinese, and you might have heard of that port in Cambodia that China will build into a naval facility.

Point number four concerns Huawei and its predominance in 5G technology. Huawei’s chairman has a vision in its own right and wants his company to dominate the global broadband market and help the Chinese ecosystem to thrive beyond the country’s borders. It is poised to constitute the virtual Belt and Road, which will naturally have to be part of the grander project, namely the area across Eurasia, Middle East, and Africa being connected on high-speed internet.

It is in the nature of all these new so-called platform businesses that are almost infinitely scalable around the planet, represented by US giants such as Amazon, Google, Facebook etc. And in China, state-sponsored technology implemented by companies like Huawei are building such an ecosystem for predominantly Chinese platform businesses to prosper, such as Tencent, Alibaba… you name them. And this is going to be huge. Alibaba already commands 3 times the GMV of Amazon!

So, the basic message is… It is only logical that China is interested in expanding this ecosystem, and in a truly networked world that will bring along and integrate a whole array of sectors from e-commerce, finance, logistics, services, as well as integrate large parts of the global labour pool. Physical trade routes are as much a part of the equation as will be the broadband network to support predominantly Chinese but also other businesses to thrive on.

Maybe a last point on BRI and geopolitics. For the Chinese to effectively build-out its vision it will need to be comfortable with the security predominantly of its maritime routes. This is clearly what all the fuss is about in the South China Sea. It is probably China’s most existential backyard. Why would China as an emerging super power not demand the same privileges as America does, much like the Monroe-doctrine that prohibits any foreign intervention in Latin America as Washington’s own perceived backyard?

The other important development here is Russia’s opening up of the Northern Sea Route as an alternative to the waterways in the Southern hemisphere. And in the future, China and Thailand may even implement an infrastructure project that has been planned for the better part of 100 years, namely to build a canal at the narrowest point of the Malaysian peninsula. It would cut short shipping times through the Strait of Malacca and circumvent lots of security issues.

To be sure, there are lots of Cassandras out there downplaying the BRI project, and naturally many things can go wrong… but Belt and Road is already starting to become a game-changer for our world and, considering the execution capabilities of the Chinese, I don’t think we have seen anything yet.