In many ways, it is a good thing that the Azzurri won the European championship. We would not have heard the end of it if the Brits had taken the trophy to their now so independent island, and if anyone really needed a morale boost on the Old Continent, it was Italy. So, good on them that the cup was granted to a nation that certainly had more of its fair share of the pandemic burden and needed every motivation to dig itself out of that hole.

Mario Draghi must be delighted with the football backwinds. The only problem, however, is that a win on the field does not necessarily heal the economic and financial wounds the country keeps suffering from. Draghi must feel like the new foreman on a construction site where sort of nothing has been built for the better part of two decades. The economy has basically not grown since the turn of the century, and I am not even kidding.

To be sure, the growth consensus for 2021 is somewhere around 5%, which sounds decent, but in light of the -9% contraction in the pandemic year 2020, this is modest at best. And that forecast is probably based on the expected inflows from the EU recovery fund, of which round about 200 billion are destined to be allocated to Italy. Those joint and several liabilities of all EU countries constitute a windfall for all recipients and aren’t even accounted for in the national books.

If they were, the divergence of fiscal efforts compared with economic output would become immeasurable. In any case, the actual government debt load of Italy has just reached another all-time high at 2.69 trillion Euros, the biggest such debt mountain in Europe. The debt-to-GDP ratio is estimated to climb to 160% in 2021, clearly an unsustainable scenario. Foreign ownership of Italian bonds has shrunk to 30%, ie the rest is more or less carried by the ECB.

After a whole decade house prices are still below the eurocrisis levels. Admittedly, Spain’s have not recovered either but still trade a notch above Italy’s. Portugal’s, on the other hand, gained 50%, and Germany’s went up like a rocket. Shareholders in Italy have literally made no money either. Adjusted for dividends the main stock index grew a mere annualised 1-1.5% in value. Facebook is worth more than the entire Italian equity market capitalisation. Tesla is kind of on par.

Youth unemployment, a dilemma across the periphery since the eurocrisis, has worsened again. Italy’s recaptured the 30% threshold and re-joined Spain and Greece in their 30s%. It is now twice as high as the eurozone average and more than four times of Germany’s which runs at 7.5%. No wonder, though, as Italy commands one of the worst demographics on the old Continent. Dependency (over 64s / 15-64 year olds) stands at 36.4%, and pensions make up for 17% of GDP, the EU’s worst ratios.

Interesting and unusual is the fact that Italy has been running a trade surplus for a while. It has clocked up 70 billion Euros on a 12-month rolling basis. Exports account for 1/3 of GDP now, and the country even sports occasional black numbers with Germany. Why then, you will ask, is the eurosystem running such vast imbalances by way of Target2? Well, it only tells us that capital flight from Italy to Germany is still outperforming the trade balance by a margin.

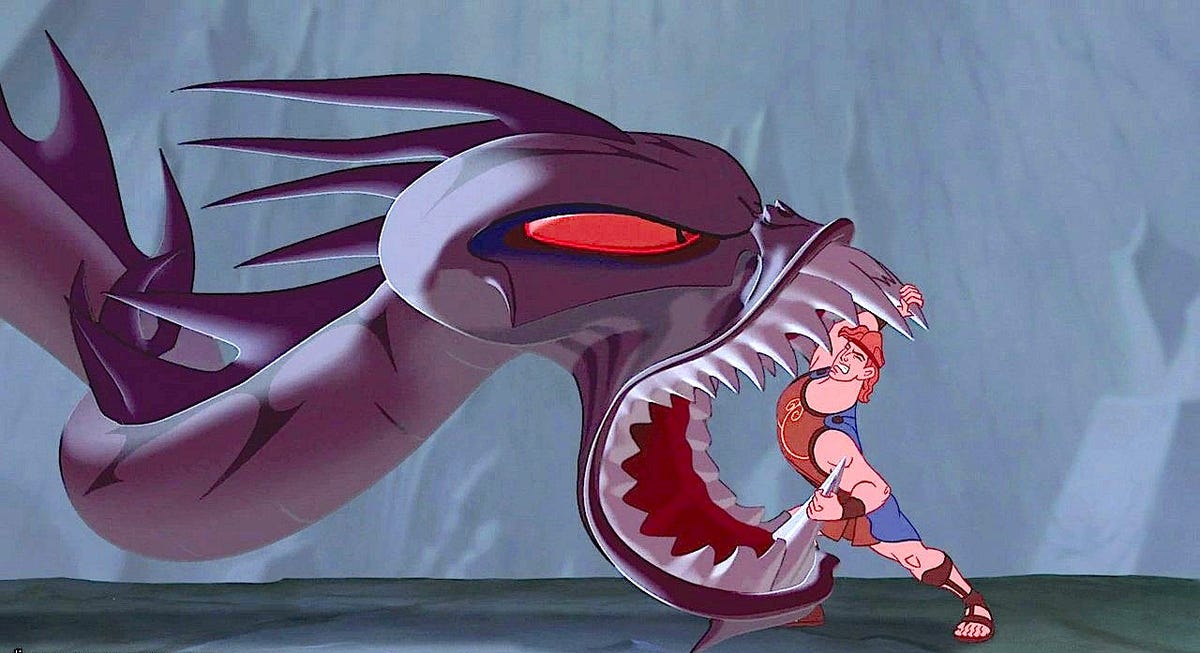

Draghi is Italy’s last hope, or so they say. He will have to perform a herculean task to right the countless wrongs. As we hear, he has begun to sink his teeth into the country’s archaic bureaucracy. Then, he will need to reverse the money flows and re-attract investments. But most importantly, he needs a change in the nation’s mind and business model. Italy still hasn’t bid farewell to think that it can be competitive by constant currency devaluations like this has worked during the 40 years before the currency union.

Sure, the ECB, under Draghi’s control, has managed to re-create the old world for a while and cushioned the blow of a fixed exchange regime by way of his super-dovish monetary policy lifeline. But now, as the prime minister, he will have to prioritise productivity progress as the feature that can save Italy’s economy and people.